Overview of Nanomaterials Synthesis Methods

Nanomaterials behave in unique ways when at least one dimension is between about 1 and 100 nanometers. At this scale, familiar materials can show very unfamiliar optical, electrical, and chemical properties. To take advantage of these effects, we need reliable ways to synthesize nanostructures with controlled size, shape, and composition. Many of the concepts described here are covered in detail in standard nanomaterials texts and reviews [1–3].

This article gives a broad overview of the major families of nanomaterial synthesis methods in a way that’s accessible to readers with a general college-level science or engineering background. We will focus on:

- Top-down vs. bottom-up concepts

- Physical and gas-phase methods

- Liquid-phase chemical methods

- Biological and green synthesis

- Template-assisted and self-assembly approaches

- Emerging and hybrid strategies

1. Big Picture: Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up

Almost all nanomaterial synthesis approaches can be grouped into two conceptual families: top-down and bottom-up methods [1,2].

In top-down approaches, you start from a bulk solid—like a crystal, wafer, or piece of metal—and physically or chemically break it down to the nanoscale. This is conceptually similar to sculpting a statue from a block of stone, but at nanometer dimensions. Examples include mechanical milling, lithography, and focused ion beam machining.

In bottom-up approaches, you start from atoms, ions, or molecules and build up the nanostructure by chemical reactions, self-assembly, or deposition from gas or solution. This is more like growing a crystal than carving one. Methods such as sol–gel, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and biological synthesis fit in this category [1–3].

A second, overlapping way to classify methods is by the type of process:

- Physical methods – based on evaporation, sputtering, milling, or ablation.

- Chemical methods – based on reactions in gases or liquids (often bottom-up).

- Biological / green methods – using plants, microbes, or other eco-friendly routes [4,5].

No single synthesis route is universally “best.” The choice depends on what form you need (powder, film, nanowire), how much control you require, the available equipment, and constraints such as cost and environmental impact.

2. Top-Down Methods

2.1 Mechanical Milling and Ball Milling

One of the simplest approaches to obtaining nanoscale powders is mechanical milling, particularly high-energy ball milling [1,2]. In this method:

- Bulk powder (e.g., metal, ceramic, alloy) is placed in a hardened jar with heavy balls.

- The jar is shaken or rotated at high speed.

- Collisions between the balls and powder repeatedly fracture the particles.

After enough time, many particles reach the nanometer range. This method is especially common for tough, high-melting materials such as ceramics and intermetallic compounds.

Advantages:

- Relatively simple and low cost.

- Can handle hard, high-melting-point materials.

- Scalable for producing large quantities of powder.

Disadvantages:

- Broad particle size distribution.

- High density of defects and strain in the particles.

- Possible contamination from the milling media.

2.2 Lithography and Etching

Lithography is the workhorse of the microelectronics industry. When pushed to its limits, it can produce structures with nanometer-scale dimensions [3]. Typical steps are:

- Coat a flat substrate with a light-sensitive polymer (photoresist).

- Expose the resist through a mask using light, electrons, or another beam.

- Develop the pattern so selected regions of resist are removed.

- Transfer the pattern into the underlying material by chemical or plasma etching.

Several lithographic approaches exist:

- Photolithography – uses UV light and masks; extremely mature and widely used for integrated circuits.

- Electron-beam lithography – draws patterns with a focused electron beam; slow but enables very high resolution.

- Nanoimprint lithography – “stamps” a pattern into a polymer and cures it; relatively simple and promising for certain nanostructured devices.

Lithography is almost always combined with etching, which removes material where the resist has been cleared. Together, they form a powerful top-down toolkit for creating nanowires, nanodots, and complex device structures with precise positioning [3].

2.3 Laser Ablation and Arc Discharge

Other top-down physical methods use extreme energy inputs to break apart solids and form nanostructures.

In laser ablation, an intense pulsed laser is focused on a solid target in vacuum, gas, or liquid. The surface material is vaporized, forming a hot plasma plume. As this plume cools, atoms condense into nanoparticles that can either deposit as a thin film or be collected as a powder [1,2].

In arc discharge, a high-current electrical arc is struck between two electrodes (often carbon). The intense heat vaporizes material from the electrodes, and cooling leads to formation of species such as fullerenes or carbon nanotubes [3].

These methods generally produce high-purity materials, since no chemical precursors or surfactants are required, but they can be energy-intensive and sometimes offer limited control over particle size distribution.

2.4 Focused Ion Beam and Related Tools

At the finest end of top-down processing, focused ion beam (FIB) tools can “mill” or “write” nanostructures directly into solid materials by sputtering atoms away. FIB is widely used to prepare high-quality samples for transmission electron microscopy and to prototype tiny device features. However, it is too slow and expensive for large-scale nanomaterial production.

3. Bottom-Up Physical and Gas-Phase Methods

3.1 Physical Vapor Deposition (PVD)

Physical vapor deposition (PVD) covers a family of techniques where a solid material is converted into a vapor and then condensed onto a substrate as a thin film or as nanostructures. Common PVD methods include:

- Thermal or electron-beam evaporation – evaporates material from a hot source in vacuum.

- Sputtering – uses energetic ions to knock atoms out of a solid target.

- Pulsed laser deposition – a form of laser ablation that deposits material onto a substrate [1,2].

By tuning the deposition rate, substrate temperature, and ambient gas pressure, PVD can produce nanocrystalline thin films, multilayers, and sometimes columnar nanostructures [3].

Strengths: high purity, good control of thickness and composition, and compatibility with many substrates. Limitations: mainly suited for thin films rather than large amounts of free nanoparticles, and it requires vacuum systems and specialized equipment.

3.2 Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD) and Atomic Layer Deposition (ALD)

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) is a foundational technique for microelectronics and many nanomaterials. In CVD, gaseous precursors flow over a heated substrate, where they react or decompose to form a solid film [1,3].

CVD is used to deposit:

- Silicon and silicon dioxide layers for integrated circuits.

- Carbon nanotubes and graphene on metal catalysts.

- Nitrides, carbides, and complex oxide films.

Variants include:

- Metal–organic CVD (MOCVD) – uses metal–organic precursors for compound semiconductors and complex oxides.

- Plasma-enhanced CVD – employs a plasma to drive reactions at lower substrate temperatures.

- Atomic layer deposition (ALD) – feeds gaseous precursors in self-limiting pulses, adding (roughly) one molecular layer per cycle. ALD enables ultrathin, highly conformal coatings on complex 3D structures with near-atomic-level control [1,3].

CVD and ALD are often used to create nanoscale films and one-dimensional nanostructures such as nanowires and nanotubes on patterned substrates.

3.3 Gas-Phase Nucleation and Aerosol Methods

In gas-phase synthesis, nanoparticles are formed directly in the gas phase via high-temperature reactions followed by cooling and nucleation. Representative methods include:

- Flame spray pyrolysis – sprays metal precursors into a flame to form oxide nanoparticles.

- Aerosol reactors – carry precursors in a gas stream that passes through heated regions to form particles.

- Inert gas condensation – evaporates metals into a cold inert gas, allowing atomic clusters to form and then condense as nanoparticles [1,2].

These approaches can produce large quantities of nanopowders such as TiO2 and SiO2, widely used in catalysis, pigments, and electronics. They are inherently continuous and scalable, although controlling aggregation and narrowing the size distribution can be challenging.

4. Bottom-Up Liquid-Phase Chemical Methods

4.1 Sol–Gel Process

The sol–gel process is a classic route to oxide nanoparticles, porous materials, and thin films [1,6]. A typical sol–gel synthesis involves:

- Starting from molecular precursors such as metal alkoxides or metal salts.

- Hydrolyzing the precursors to form metal–OH groups.

- Condensing these groups into an extended M–O–M network.

- Allowing the system to evolve from a sol (colloidal suspension) to a gel (solid network in a liquid).

- Drying and heat-treating the gel to obtain a solid with nanoscale features.

Modifying parameters like pH, solvent, water content, and additives allows control over particle size, porosity, and degree of aggregation. Sol–gel methods are widely used for catalyst supports, optical coatings, and nanostructured ceramics.

4.2 Precipitation and Co-precipitation

Precipitation methods form nanoparticles by driving a solute out of solution as a solid phase. For example, a solution of metal salts can be treated with a base or another reagent so that insoluble hydroxides, oxides, or sulfides form [1,2].

In co-precipitation, two or more types of ions precipitate together, enabling the synthesis of mixed oxides or doped materials. By carefully controlling supersaturation, temperature, and the presence of surfactants or polymers, it is possible to favor rapid nucleation and limit growth, leading to nanoscale particles.

Precipitation-based methods are attractive for their simplicity, low cost, and scalability, but they can yield broad size distributions and may require post-treatments such as calcination to achieve the desired crystallinity [2,7].

4.3 Hydrothermal and Solvothermal Synthesis

In hydrothermal synthesis, reactions take place in water at temperatures above its normal boiling point under autogenous pressure; solvothermal processes are similar but use organic solvents [6]. Typical conditions involve:

- Temperatures from roughly 100 °C to 300 °C.

- Elevated pressures in sealed autoclaves or flow reactors.

Hydrothermal and solvothermal methods are particularly useful for:

- Growing well-crystallized nanorods and nanowires (e.g., ZnO, TiO2).

- Producing nanoparticles with controlled shapes and facets.

- Creating hierarchical structures and porous materials [6,8].

The morphology is influenced by factors like pH, mineralizers (such as NaOH or fluorides), seed crystals, and surfactants. Continuous-flow hydrothermal systems have been developed to enable scalable production with good control over particle properties.

4.4 Microemulsions and Surfactant-Assisted Synthesis

Microemulsions are thermodynamically stable mixtures of oil, water, and surfactant that form nanometer-sized droplets. These droplets act as tiny reaction vessels:

- Metal ions dissolve in one phase (for example, the water-rich phase).

- A reducing agent or precipitating agent is in the other phase.

- Collisions between droplets allow reagents to mix and nucleate nanoparticles.

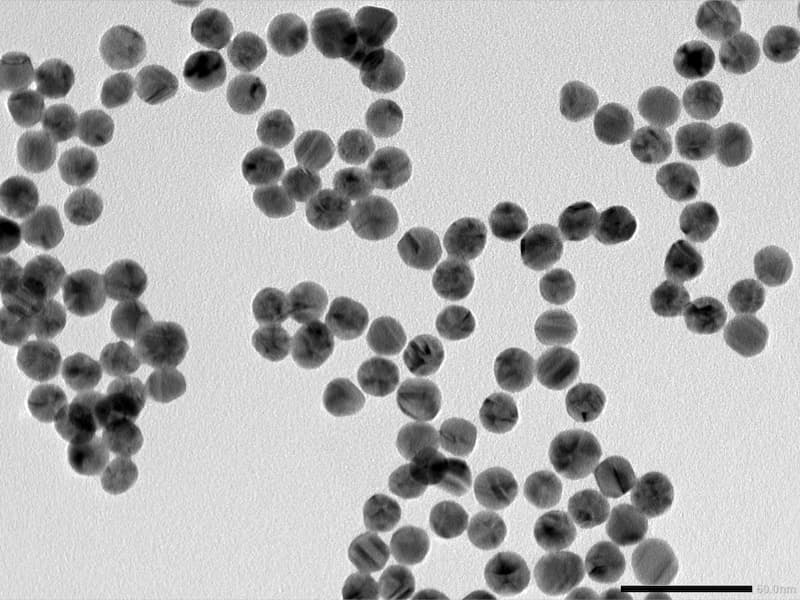

Since the droplet size is well-defined, particles formed inside them can have relatively narrow size distributions. More generally, surfactant-assisted synthesis uses molecules that bind to particular crystal faces, control growth, and prevent aggregation. This strategy is central to the colloidal synthesis of quantum dots, gold nanoparticles, and nanorods [2,3,7].

4.5 Sonochemical and Microwave-Assisted Methods

Energy input can drastically influence nucleation and growth. In sonochemical synthesis, high-intensity ultrasound produces microscopic cavitation bubbles. When these bubbles collapse, they generate localized hot spots with extreme temperatures and pressures that drive reactions and nanoparticle formation [6].

Microwave-assisted synthesis uses microwave radiation to heat solutions rapidly and often more uniformly than conventional heating. Both techniques can shorten reaction times from hours to minutes and sometimes yield unique phases or morphologies not easily accessible otherwise.

4.6 Electrochemical Methods

Electrochemistry provides several routes to nanostructures:

- Electrodeposition – reducing metal ions at an electrode to grow nanostructured films or particles.

- Template-assisted electrodeposition – using porous templates such as anodic alumina to direct the growth of nanowires inside nanoscale pores.

- Anodization – oxidizing metals like aluminum or titanium to form ordered nanoporous oxides and nanotube arrays [8].

These methods are important for creating ordered arrays of nanostructures directly on conducting substrates, which is useful in sensing, energy storage, and catalysis.

5. Self-Assembly and Soft-Matter Routes

5.1 Molecular and Colloidal Self-Assembly

Not all nanostructures need to be forced into existence; some can spontaneously self-assemble when the building blocks are designed appropriately [7].

Examples include:

- Block copolymers – polymers made from chemically distinct segments (blocks) that phase-separate into ordered nanodomains (spheres, cylinders, lamellae). These patterns can act as templates for inorganic structures.

- Colloidal crystals – monodisperse nanoparticles or polymer spheres can pack into ordered arrays, analogs of atomic crystals but at a larger scale.

Such self-assembled systems provide routes to photonic crystals, membranes, and periodic materials with feature sizes in the tens of nanometers.

5.2 Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Assembly

Layer-by-layer assembly builds thin films by alternately exposing a substrate to solutions of oppositely charged species. For instance:

- Dip a substrate in a positively charged polymer solution; the surface becomes positively charged.

- Rinse and then dip into a negatively charged nanoparticle or polyelectrolyte solution.

- Repeat to build up films with nanometer-scale control over thickness and composition.

LbL assembly is gentle, often performed in water, and works well for incorporating biological components or delicate nanomaterials [7].

6. Biological and Green Synthesis

6.1 Plant-Based Green Synthesis

Traditional nanomaterial syntheses can involve harsh chemicals, high temperatures, and organic solvents. Green synthesis aims to reduce environmental impact by using milder conditions and renewable resources [4,5].

In plant-based synthesis, extracts from leaves, fruits, roots, or other plant tissues are mixed with solutions of metal salts (such as silver nitrate). Biomolecules in the extracts act as:

- Reducing agents – converting metal ions into metallic nanoparticles.

- Stabilizers – capping and protecting the nanoparticles from aggregation.

This approach can produce stable, often biocompatible nanoparticles suitable for antimicrobial and biomedical applications. However, the chemical composition of plant extracts can vary with species, season, and extraction conditions, which can affect reproducibility.

6.2 Microbial Synthesis (Bacteria, Fungi, Yeast, Algae)

Various microorganisms can convert metal ions into nanoparticles either inside their cells (intracellular) or in the surrounding medium (extracellular) [4,5]. Enzymes, proteins, and metabolites participate in reducing the ions and controlling nucleation.

Biogenic nanoparticles often carry organic coatings that improve colloidal stability and can introduce biological functionality, such as targeting or responsiveness to specific environments. Microbial synthesis aligns with green chemistry principles but can require careful control of growth conditions and biosafety considerations.

6.3 Sustainable Nanomaterials and Circular Economy Concepts

A broader view of green nanomaterials synthesis includes:

- Using agricultural waste and biomass as cheap, renewable precursors.

- Favoring water and other benign solvents where possible.

- Designing processes with lower energy requirements and minimized waste.

- Recycling reagents and integrating nanomaterials production into circular economy frameworks [4,5].

These approaches seek to deliver the benefits of nanotechnology while reducing ecological and health footprints.

7. Template-Assisted and Hierarchical Synthesis

7.1 Hard Templates

Template-assisted synthesis uses pre-existing structures to guide the shape and arrangement of nanomaterials [3,7]. Hard templates are rigid, solid materials such as:

- Porous anodic alumina (AAO) – with highly ordered arrays of cylindrical nanopores.

- Mesoporous silica – with pore sizes in the 2–50 nm range.

By filling these pores with metals, semiconductors, or polymers (for example, via electrodeposition or sol–gel infiltration) and then removing the template, one can obtain arrays of nanowires, nanotubes, or other nanostructured architectures.

7.2 Soft and Biological Templates

Soft templates include micelles, vesicles, and other self-assembled surfactant structures that guide where and how inorganic precursors nucleate and grow. Biological templates, such as DNA strands, peptides, and virus capsids, can also organize inorganic materials into intricate nanoscale patterns [7].

These strategies often combine bottom-up chemistry with self-assembly, enabling hierarchical nanostructures with features reminiscent of natural materials.

8. Emerging and Hybrid Approaches

8.1 Microreactors and Continuous-Flow Synthesis

Instead of traditional batch flasks, microreactors and continuous-flow systems use small channels, mixers, and reactors to carry out nanoparticle syntheses with precise control over temperature, mixing, and residence time [4,6].

Continuous-flow hydrothermal or solvothermal reactors, for example, can produce large quantities of nanoparticles with tunable size and composition while potentially reducing waste and improving reproducibility. These technologies are attractive for scaling up lab recipes to pilot or industrial scale.

8.2 3D Printing and Nano-Ink Technologies

3D printing itself typically operates at the micrometer to millimeter scale, but nanomaterials enter the picture through nano-inks that can be printed as functional patterns. For example:

- Conductive inks containing silver nanoparticles or nanowires for printed electronics.

- Transparent conductive films made from nanowires or carbon nanotubes.

- Printed sensors based on metal oxide or carbon nanomaterials.

In these cases, synthesis of the nanomaterial and its formulation into printable inks are coupled with patterning via printing techniques.

8.3 Hybrid Top-Down / Bottom-Up Strategies

In many practical applications, top-down and bottom-up methods are combined. For example:

- Use a bottom-up method (such as sol–gel or hydrothermal synthesis) to produce nanoparticles.

- Employ top-down lithography to define where on a substrate the nanoparticles should be deposited or grown.

- Grow nanowires by CVD only at lithographically patterned catalyst sites.

These hybrid strategies leverage the strengths of both classes of methods—precision patterning on the macro- to microscale and controlled growth at the nanoscale—to create functional devices and materials.

9. Comparing Methods: Key Criteria

When choosing a synthesis route for a particular nanomaterial, several recurring criteria appear in the literature [1–3,7,8]:

- Size and shape control – Gas-phase and wet-chemical routes (colloidal synthesis, sol–gel, hydrothermal methods) generally offer finer control than mechanical milling. Techniques like ALD and carefully designed colloidal syntheses can approach atomic-level precision for some systems.

- Purity and defect structure – Physical vapor methods and some CVD routes can give very pure films with controlled defect densities. Mechanical milling often introduces contamination and high defect densities, which might be beneficial for certain catalytic applications.

- Scalability and cost – Ball milling, precipitation, and some gas-phase routes are relatively inexpensive and scalable. Lithography and ALD are precise but more costly and slower per unit area or volume.

- Environmental and safety aspects – Green and biological synthesis aim to minimize toxic reagents and solvents, while traditional methods may rely on organic solvents, strong reducing agents, or high energy input.

- Application-specific constraints – Biomedical uses require biocompatibility and low toxicity, favoring green or carefully controlled colloidal syntheses. Electronics demand clean, defect-controlled films, where lithography combined with CVD/PVD and ALD dominates. Catalysis and energy storage often need high surface area and porosity, making sol–gel, hydrothermal, and template-based methods popular.

10. Choosing a Synthesis Route: Practical Checklist

For a practical decision-making process, consider the following questions:

-

What form of nanomaterial do you need?

- Powders or colloidal particles: precipitation, sol–gel, hydrothermal, microemulsion, gas-phase aerosol, or green synthesis.

- Thin films or coatings: CVD, PVD, sol–gel coatings, ALD, or layer-by-layer assembly.

- Nanowires, nanotubes, or ordered arrays: template-assisted electrodeposition, anodization, lithography plus etching, or catalyst-assisted CVD growth.

-

How tight should the size and shape distribution be?

- “Roughly nanoscale” is enough: mechanical milling, simple precipitation.

- Precise control needed (e.g., quantum dots): colloidal methods, microemulsions, ALD, or advanced CVD protocols.

-

What are the environmental and safety constraints?

- Favor green synthesis, water as solvent, and lower-temperature routes when possible.

- Consider continuous-flow and hydrothermal methods to reduce waste and energy consumption.

-

What is your budget and production scale?

- Large-scale industrial: gas-phase flame synthesis, large precipitation reactors, continuous-flow sol–gel or hydrothermal systems.

- Small-scale research: lithography, ALD, and specialized CVD are more realistic.

-

What downstream processing and characterization tools are available?

- Do you have sintering furnaces, spray dryers, or cleanroom access?

- Can you safely handle organic solvents and manage waste streams?

In practice, researchers often explore multiple routes and optimize conditions until structure, properties, scalability, and cost align with project goals.

11. Conclusion

Nanomaterial synthesis is best thought of as a versatile toolbox rather than a single method. Broadly:

- Top-down methods such as mechanical milling, lithography, laser ablation, and focused ion beam start from bulk materials and refine them to the nanoscale.

- Bottom-up physical methods like PVD, CVD, and gas-phase nucleation assemble atoms and molecules into nanoscale films and particles.

- Liquid-phase chemical routes including sol–gel, precipitation, hydrothermal, microemulsion, and electrochemical methods “cook” nanomaterials in solution.

- Self-assembly and template-guided approaches use molecular interactions and pre-formed structures to create ordered and hierarchical nanostructures.

- Biological and green syntheses exploit plants, microbes, and sustainable feedstocks to reduce environmental impact.

By understanding the strengths and limitations of each approach—including control, purity, scalability, cost, and sustainability—researchers and engineers can select or combine methods that best match their scientific and practical requirements. As new techniques such as microreactors, hybrid top-down/bottom-up processes, and advanced green chemistry continue to evolve, the nanomaterials toolbox will only become richer and more powerful.

References

- G. Cao and Y. Wang, Nanostructures and Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Properties and Applications, 2nd ed., World Scientific, 2011.

- C. N. R. Rao, A. Müller, and A. K. Cheetham (eds.), The Chemistry of Nanomaterials: Synthesis, Properties and Applications, Wiley-VCH, 2004.

- M. C. Roco, R. S. Williams, and P. Alivisatos (eds.), Nanoscale Science and Engineering: Towards a New Paradigm in Manufacturing, Kluwer Academic, 1999.

- A. Albanese, P. S. Tang, and W. C. W. Chan, “The effect of nanoparticle size, shape, and surface chemistry on biological systems,” Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering, 14, 1–16 (2012).

- P. K. Jain, X. Huang, I. H. El-Sayed, and M. A. El-Sayed, “Review of some interesting surface plasmon resonance-enhanced properties of noble metal nanoparticles and their applications to biosystems,” Plasmonics, 2, 107–118 (2007).

- K. Byrappa and M. Yoshimura, Handbook of Hydrothermal Technology, William Andrew Publishing, 2001.

- N. Pinna and M. Niederberger (eds.), Metal Oxide Nanoparticles in Organic Solvents: Synthesis, Formation, Assembly and Application, Springer, 2009.

- P. Roy, S. Berger, and P. Schmuki, “TiO2 nanotubes: Synthesis and applications,” Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 50, 2904–2939 (2011).

- H. Cölfen and S. Mann, “Higher-order organization by mesoscale self-assembly and transformation of hybrid nanostructures,” Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 42, 2350–2365 (2003).

- P. T. Anastas and J. C. Warner, Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, Oxford University Press, 1998.